(A yoga guru with a following of millions, Baba Ramdev has combined business savvy and India’s interest in traditional medicine to build a consumer goods empire. His agenda promotes economic nationalism.)

Haridwar, Uttarakhand – White-robed monks with tonsured heads shuffle to their classes on Hindu scriptures at Yoga Guru Baba Ramdev’s sprawling headquarters fringed with palm trees in Haridwar, an ancient city on the banks of the Ganges river.

It’s not so peaceful nearby, where workers frantically haul goods onto trucks at the guru’s 60-hectare plant, factory and warehouse site. Guards warn you to stay clear of the loading areas or risk being caught in an hours-long traffic jam. Endless columns of trucks are rolling out to different parts of India. The site employs 10,000 workers.

India’s most popular guru, Ramdev, is not a typical Hindu holy man. He straddles the spiritual and material worlds, looming large in India’s public space, promoting the Hindu culture and lifestyle.

Ramdev is decidedly political. He campaigned for the Hindu nationalist Bharatiya Janata Party in the 2014 elections and is known to be close to Prime Minister Narendra Modi.

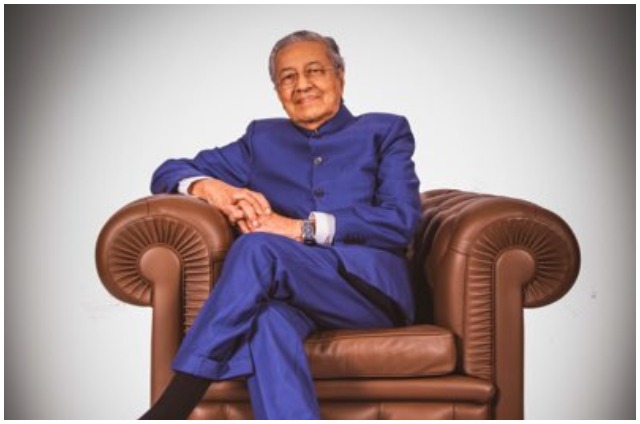

Guru business – Acharya Balkrishna, chairman of Patanjali Ayurvedic Limited, in a phone call during an interview at the company headquarters in Haridwar in northern Uttarakhand state, India. Behind him is a framed image of Baba Ramdev, the company’s co-founder, in a yoga pose. (photo: dpa)

Ramdev rose to fame with his yoga programmes on TV in the early 2000s and teamed up with his close associate, Acharya Balkrishna, to manufacture drugs based on Ayurveda, a system of Indian traditional medicine.

Patanjali brand created in 2006

In 2006, the duo set up Patanjali Ayurved Ltd, which now offers over 500 products derived from herbal and organic recipes, ranging from face-creams, toothpaste, soaps and shampoos to modern convenience foods like instant noodles.

Growing at 150 per cent annually, Patanjali has emerged as India’s fastest growing and diversifying consumer products behemoth, outpacing multinational investors.

“Nobody believed that a domestic company could beat foreign companies. The Baba, after making people do yoga poses, is now making these big companies do the Sirsasana (headstand pose),” boasts saffron-robed and bearded Ramdev as a posse of stern bodyguards look on.

Patanjali is logging 50 billion rupees (750 million dollars) in annual sales and hopes to double its turnover this financial year, driven by perceptions that its products are healthier and chemical-free, even as they are up to 30 per cent cheaper than similar lines.

Ramdev also dented rivals’ market shares by simultaneously propagating the “Swadeshi” movement – Hindi for Made in Our Own Country – a campaign to shun foreign goods to boost the country’s self-reliance.

Indians have found such campaigns appealing since the British colonial era.

“We attained political independence in 1947, but the struggle for economic independence continues,” declares Ramdev, his tone and expression suddenly turning grave.

“We still have poverty and a form of corporate colonization. These big companies reap profits here and send them abroad. The money of this country should stay in the country,” he said in an interview in Delhi.

Ramdev asserts Patanjali is not a conventional business – unlike international companies which chase profits and are little concerned about people – adding that business success is no contradiction with his life as a clergyman.

“We do not seek personal wealth. Our goal is a healthy being and a wealthy nation. It is a selfless service, a form of patriotism,” says Ramdev, who owns no stake in Patanjali.

“We provide employment, setting up education institutes, funding research on diseases and donating charity for poor destitute and handicapped people, not filling someone’s pockets”.

Business analysts call Patanjali a “great disruptor” in the fast-moving consumer goods category, attributing its success to an efficient supply chain and local sourcing. The group has a 20-25 per cent cost advantage due to savings in distribution.

This gives the company leverage to price its products cheaper, Ruchita Maheshwari from the IIFL brokerage says.

A loyal base comprising 10 million middle-class urban consumers, a low-cost advertising strategy that relies on word-of-mouth publicity and Ramdev’s exhortations and a growing market for Ayurveda, are factors behind Patanjali’ success.

“Patanjali’s key focus appears to be mainly on growth and less on profits,” she says. “Our products are bought by the rich, middle- as well as lower-income strata. It is one brand which is used by the CEO boss and even his driver.

“That is the power and unique selling point of the Patanjali brand,” Patanjali chairman Acharya Balkrishna, who owns over 90 per cent.

Ramdev insists Patanjali is less about eating into market shares than building new markets for products such as Amla juice (Indian gooseberry thought to boost immunity) and cow’s ghee (clarified butter) by telling people of the substances’ health benefits and popularizing their use.

“What makes Patanjali a credible threat is that it does not try to beat other FMCG companies at their game; it changes the game for them,” IIFL said in a report.

Controversies still surround Ramdev

Ramdev is not free of controversy. Critics accuse Ramdev of promising cures for fatal diseases like AIDS and cancer. Mindful of the opposition to same-sex relations in the majority Hindu nation, he also claims to cure even homosexuality, which he terms a disease.

According to social scientist Shiv Visvanathan, Ramdev is the first guru to make the transition from the symbolic presentation of India’s civilizational ethos and ideas to actual production.

Encouraged by their wide reach through television in recent years, Indian gurus and holy men like Sri Sri Ravishankar and Gurmeet Ram Rahim Singh have launched their own consumer products lines, mostly based on organic and herbal materials.

But the other Guru businesses lag behind Patanjali, an early mover, and have a long way to go to emulate Ramdev’s success.

IIFL projects Patanjali’s turnover to quadruple to 200 billion dollars by 2020 on the back of ever-increasing demand and plans to set up a bigger retail and distribution network and more food parks.

Ramdev who reportedly once sold herbal tonics from a bicycle, now openly says he aims to upstage giants including the Unilever subsidiary Hindustan Lever, India’s largest consumer goods company.

Multinational companies (MNCs) remain discreet. Of the handful contacted not one chose to comment directly on Ramdev’s aggressive stance.

“Patanjali is giving such competition to the MNCs. It will shut the gate in Colgate,” Ramdev jokingly warned recently. “The bird in Nestle’s logo will fly away in a year’s time. The lever in Unilever, will also collapse in three years.”

– dpa