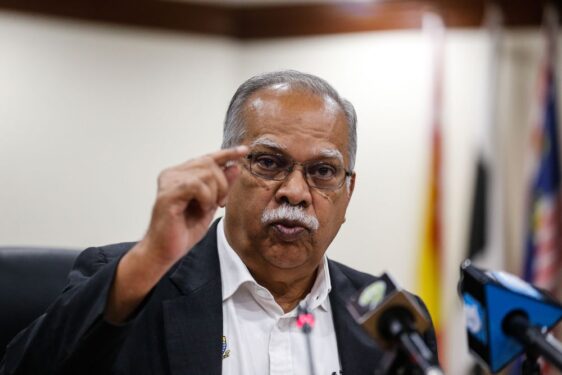

MEDIA STATEMENT BY PROF DR P.RAMASAMY

CHAIRMAN, URIMAI PARTY

It is both surprising and unsurprising that Barisan Nasional’s (BN) Umno made a strong comeback in the recent Air Kuning by-election.

In the by-election held on April 26, 2025, despite a lower voter turnout, Umno managed to double its share of votes compared to the 2022 general elections. In contrast, Perikatan Nasional’s (PN) PAS candidate underperformed, losing about 800 votes compared to their 2022 showing.

While Parti Sosialis Malaysia (PSM) lost its deposit, it notably doubled its vote count compared to the last elections. However, its articulation of class-based issues was no match for the entrenched divisive politics championed by both BN and PN.

Despite PN’s impressive gains in the last general and state elections, the coalition appears to have reached a political saturation point. Its failure to transcend ethnic and religious narratives remains its major stumbling block. PN repeatedly failed to capitalize on the political, social, and economic frustrations prevalent among the non-Malay communities.

It is not that Chinese and Indian voters are particularly satisfied with the Pakatan Harapan (PH)-led coalition government. Rather, PN has simply failed to position itself as a credible alternative within the political vacuum that exists.

A misstep during the campaign further hurt PAS’s standing: the party’s decision to raise the issue of pig farms in the Air Kuning constituency alienated the Chinese community, which makes up 22% of voters. PAS perhaps thought that touching on sensitive matters would consolidate its appeal among Malay-Muslims. Yet, the move backfired. Malays did not shift en bloc to PN but remained largely loyal to Umno and BN.

Despite PAS’s long-standing presence in Malaysian politics, the party seems unable to strategize beyond narrow ethno-religious lines. How can PN hope to present itself as an alternative to PH when it repeatedly fails to grasp and respond to the larger political dynamics?

Whatever criticisms are leveled against BN or Umno, it must be acknowledged that they retain deep-rooted strength in certain Malay-majority areas. Their extensive patronage networks, despite the coalition’s overall political decline, continue to play a crucial role. In Perak, particularly in constituencies like Air Kuning, these networks help maintain vital ties with the Malay community.

Umno’s control of the Perak state government also offered a significant advantage. Furthermore, although turnout among Chinese and Indian voters declined, BN’s patronage networks through MCA, MIC, and even some informal DAP channels played a role in drawing non-Malay support.

The MIC, under the stewardship of its deputy president and Tapah MP M. Saravanan, proved particularly effective in consolidating Indian support for BN. Nevertheless, it is important to note that around 500 voters shifted their support from MIC to PSM — a development partly attributed to Urimai’s grassroots efforts to engage disgruntled sections of the Indian community.

BN’s victory in the Air Kuning by-election was less about its growing popularity and more about its effective use of government machinery and patronage — a familiar pattern in Malaysian politics.

However, the outcome of this “buy-election” is not necessarily a reliable indicator of future voting trends. Malaysian politics remains volatile, and unexpected shifts could still occur before the next general election.